This is the first part of a two-part series on two early science fiction writers: C.S. Lewis and H.G. Wells. While they were both British novelists in the early 20th century, they had quite different worldviews. Part 1 discusses C.S. Lewis’ reading of Wells and the basic plotline of The War of the Worlds, Wells’ first science fiction novel. Part 2 presents some of Wells’ themes and Lewis’ critique of “Wellsianity.”

Our Eschatological Age

We live in an apocalyptic age, filled with post-9/11 politics, economic catastrophes, great droughts, deadly storms, genocidal earthquakes, and  nuclear threats. We live in an age when a wave from the sea can wipe out a generation of technological imperialism, and when the cryptic astronomical observations of an ancient Mesoamerican culture can move people to look to the skies again. Then there is Israel, and Tim Lahaye, and the evident death of popular music. It might not actually be the Last Days, but it sure feels like it.

nuclear threats. We live in an age when a wave from the sea can wipe out a generation of technological imperialism, and when the cryptic astronomical observations of an ancient Mesoamerican culture can move people to look to the skies again. Then there is Israel, and Tim Lahaye, and the evident death of popular music. It might not actually be the Last Days, but it sure feels like it.

Taking advantage of our culture’s eschatological leanings, I teach a class on the End of the World most every year. One of the reading options is H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds. This summer’s discussion was particularly good, as students drew from the deep waters of Wells’ social  critique. His stories are not just stories for art’s sake—they do something, they tell truth from his perspective.

critique. His stories are not just stories for art’s sake—they do something, they tell truth from his perspective.

So it was in rereading The War of the Worlds this year as I was reading through Lewis’s Ransom Trilogy (also called the Space or Cosmic Trilogy) that I saw how clearly Lewis was responding to Wells. As a fan of H.G. Wells’ literature, C.S. Lewis was taking the classic Martian tale and inverting it. Lewis turned The War of the Worlds upside down, providing his own interplanetary romances that subvert Wells’ perspective on truth.

Becoming a Fan

While the victim of a maniacal bullying schoolmaster who had the impressive inability to broaden pupils’ minds—at a school C.S. Lewis called “Belsen” after the concentration camp—the young Lewis found solace in the scant reading material that was available. Among his discoveries that stuck for life was H.G. Wells. In his autobiography he reflects on the experience:

“What has worn better, and what I took to at the same time, is the … the ‘scientifiction’ of H. G. Wells. The idea of other planets exercised upon me then a peculiar, heady attraction, which was quite different from any other of my literary interests” (Surprised by Joy 38).

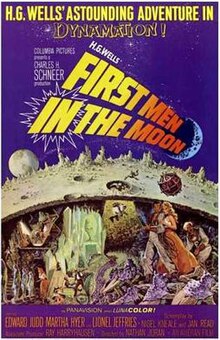

At eleven, Lewis devoured Wells’ First Men in the Moon, a gift from his father. When he was sixteen, his best friend Arthur sent him a copy of The Country of  the Blind and Other Stories. We see in this prep school teenager the beginnings of both literary friendship and literary criticism:

the Blind and Other Stories. We see in this prep school teenager the beginnings of both literary friendship and literary criticism:

“I have only just discovered that you put my name in that book. If I had seen it earlier I shd. have sent it back. You have no right to be so foolishly generous! However–many, many thanks. When one has set aside the rubbish that H. G. Wells always puts in, there remains a great deal of original, thoughtful and suggestive work in it. The ‘Door in the Wall’, for instance, moved me in a way ‘Door in the Wall’, for instance, moved me in a way I can hardly describe! How true it all is: the SEEING ONE walks out into joy and happiness unthinkable, where the dull, senseless eyes of the world see only destruction & death. ‘The Plattner Story’ & ‘Under the Knife’ are the next best: they have given me a great deal of pleasure” (Letter to Arthur Greeves c. Sept 26, 1914).

As an established writer on the heels of writing his Cosmic Trilogy and The Screwtape Letters, Lewis describes his debt to H.G. Wells in a letter to Ruth Pitter (Jan 4, 1947). And in a letter to Arthur in 1931, Lewis admits that H.G. Wells’ romances were “almost his first love.” Lewis didn’t always love Wells’ stories, but he always found they engaged his attention and helped him in his intellectual search, as we see here:

“You will be surprised when you hear how I employed the return journey–by reading an H. G. Wells novel called ‘Marriage’, and perhaps more surprised when I say that I thoroughly enjoyed it; one thing you can say for the man is that he really is interested in all the big, outside questions–and the characters are intensely real, especially a Mr Pope who reminds me of Excellenz [a derogative term for his father]. It opens new landscapes to me–how one felt that on finding that a new kind of book was waiting for one, in the old days–and I have decided to read some more of his serious books” (Letter to Arthur Greeves c. Feb 3, 1920).

Christian Disagreement with Wells

As a Christian, Lewis found great disagreement with H.G. Wells, a Darwinian atheist. While they had once shared intellectual quarters, Lewis found that the greatest authors in his world were this strange breed of intellectual called “Christian.”  In a sense, Lewis’ relationship with Wells is part of his conversion:

In a sense, Lewis’ relationship with Wells is part of his conversion:

“On the other hand, those writers who did not suffer from religion and with whom in theory my sympathy ought to have been complete—Shaw and Wells and Mill and Gibbon and Voltaire—all seemed a little thin; what as boys we called ‘tinny.’ It wasn’t that I didn’t like them. They were all (especially Gibbon) entertaining; but hardly more. There seemed to be no depth in them. They were too simple. The roughness and density of life did not appear in their books” (Surprised by Joy 202).

Lewis’ developing disagreement with Wells was profound. He adopted the Inklings term, “Wellsianity,” to describe in his essays “Is Theology Poetry” and “The Funeral of a Great Myth” the scientific myths of progress in his age as betrayed by Wells’ literary social Darwinism. Lewis disbelieved in progress, argued that things were not actually progressing (WWII would later become evidence), and was incredulous that people thought that technological progress could bring about human improvement. He was very much an anti-Wells writer.

At a deeper level, though, Lewis engages in Wells in his fiction, and quite clearly does so in the Ransom Trilogy, turning The War of the Worlds inside out to retell the story of what it means to be human.

H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds

Wells’ own understanding of humanity is clear throughout his work, and especially in his 1898 novel The War of the Worlds. Wells’ contemporaries  viewed their Western culture as the pinnacle of human society. But, in Wells’ narrative, that view is put into a new context:

viewed their Western culture as the pinnacle of human society. But, in Wells’ narrative, that view is put into a new context:

“No one would have believed in the last years of the nineteenth century that this world was being watched keenly and closely by intelligences greater than man’s and yet as mortal as his own; that as men busied themselves about their various concerns they were scrutinised and studied, perhaps almost as narrowly as a man with a microscope might scrutinise the transient creatures that swarm and multiply in a drop of water…. With infinite complacency men went to and fro over this globe about their little affairs, serene in their assurance of their empire over matter” (7).

These Watchers are also Actors, and vastly superior to us:

“Yet across the gulf of space, minds that are to our minds as ours are to those of the beasts that perish, intellects vast and cool and unsympathetic, regarded this earth with envious eyes, and slowly and surely drew their plans against us” (8).

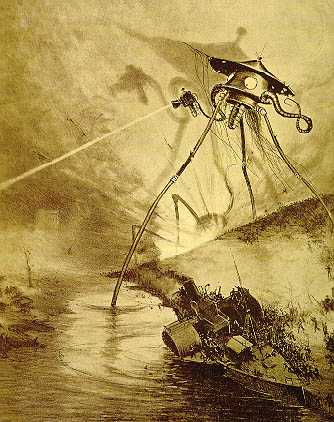

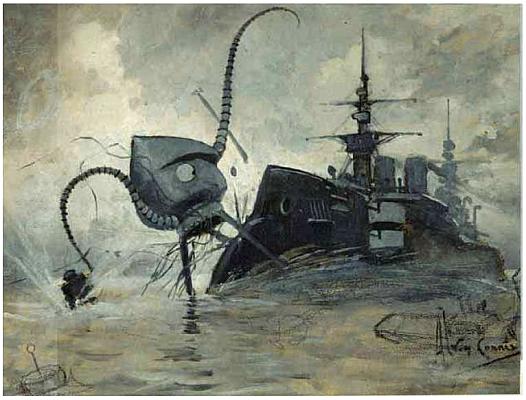

The stage is well set, and the plotline is fairly simple. Martians invade with such vastly superior weaponry and armor that the British militia is almost  entirely useless against them. The Martians—rotund fleshly bodies that telepathically operate terrifying, giant tripod—roam through the English countryside toward London planting Martian vegetation, wasting entire villages, and capturing humans to feed upon as a spider feeds on the insects in her web. “This isn’t a war,” one character exclaims. “It never was a war, any more than there’s war between man and ants” (173).

entirely useless against them. The Martians—rotund fleshly bodies that telepathically operate terrifying, giant tripod—roam through the English countryside toward London planting Martian vegetation, wasting entire villages, and capturing humans to feed upon as a spider feeds on the insects in her web. “This isn’t a war,” one character exclaims. “It never was a war, any more than there’s war between man and ants” (173).

See part 2 here.